One of the key components to making a good integration between products is understanding the mental model of each product. What one product calls a “counter” another could call a “metric” or a “stat”, for example; or worse, one product could be reporting, say, the amount of free memory, while another is reporting the percentage.

The same goes for integration points between teams. When I built our previous release pipeline, I discovered very quickly that while developers were comfortable talking about repositories, operations thought in terms of applications, and neither knew nor cared how many moving parts went into a single app so long as it was all on a server together. This resulted in a system in which devs had to create a long, complex manifest to explain to ops exactly what code should be deployed by the night shift when, and a number of errors came out of that process.

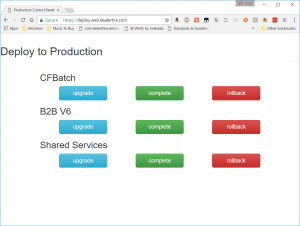

I knew if I had per-container deploy buttons in production, like I did for pre-production, we’d have similar issues. Developers want to push single containers out into test environments, but operations wants to deploy a single application, with as little fuss as possible, and a quick painless rollback if they notice problems. So when it came time to move to containers in production, I designed them a custom application to do just that. I called it Deploybot.

Rancher ships with a catalog of common apps that you might want to deploy in your container environment. It also comes with the ability to make your own catalogs. A catalog consists of a docker-compose and a rancher-compose; the former is a standard format for spinning up a set of containers that depend on each other as a single unit, while the latter is a Rancher-specific extension to the format that allows the product to add extra metadata to the containers once they’re spun up. In the GUI, the catalog makes it really simple to deploy a whole application at once: just a few clicks and you can have a running app within seconds. Furthermore, when new versions are released to the catalog, it’s only two clicks to upgrade to the new version, which updates only those containers which have changed.

Not only does this let us quickly upgrade, it keeps a history of everything that’s ever been deployed. This means we can easily spin up a version in develop that is identical to this week’s production environment — or last week’s, or next week’s. Furthermore, we can roll back easily to a given deployment in the event of an emergency, and we have a record in the UI of every deploy that’s been done.

I determined quickly that the API would let me upgrade from the catalog if a new version had been pushed. From there, my biggest problem was logistics. Let’s say an app has 4 containers in it. At present, we had 4 build plans, each of which built a single container and pushed it to artifactory. When deploying a container at a time, we could easily just use the Rancher API to push that container to our test environment. But for a catalog update, things were more complicated.

Step 1: Mark for Release

The first problem: how do we determine if a container has passed testing when the final phase of our testing is still manual? Artifactory has a system of properties on a given artifact; you can do a search using the API for only containers that have a given property. So I added a deploy target called “Mark for Release” after our development and test targets; when a given asset is ready to go to production, the lead developer for the team “deploys” to that “target”. Because I’m a masochist, I did this in node.js:

addLabel (args) { // eslint-disable complexity no-console

if (!args || !args.container || !args.version || !args.label || typeof args.value === 'undefined') {

return Promise.reject(new Error('Incorrect parameters: please supply container, version, label, and value'));

}

console.log(`Adding label ${args.label}=${args.value} to ${args.container}:${args.version}`);

const {container, version, label, value} = args;

return request({

method: 'PUT',

uri: `${opts.uri}/artifactory/api/storage/docker-local/${container}/${version}?properties=${label}=${value}`,

auth: {

user: opts.user,

pass: opts.password,

sendImmediately: true

}

});

}

This is just a wrapper around a PUT request to artifactory; docker-local is our local docker repository, as you can tell by the oh-so-creative name. Later logic will pull the list of items with that label and find the highest-numbered container that is ready to be released. At first, this worked great… right up until someone decided they wanted to fall back to an older version of a container and we had to manually remove the label from the newer container. Then I added guard conditions:

markForRelease (artif, args) {

return artif.addLabel({

container: args.container,

version: args.ver,

label: 'release',

value: 'true'

}).then(() => artif.getAllItemsByLabel('release', 'true'))

.then((items) => artif.filterDockerResults(items))

.then((containers) => {

const promises = containers.map((item) => {

const [, name, version] = artif.parseVersion(item);

// Guard: only replace the current container, with versions higher than this one

if (name !== args.container) return Promise.resolve();

if (Number(version) <= Number(args.ver)) return Promise.resolve();

return artif.addLabel({

container: args.container,

version: item.substring(item.lastIndexOf('/') + 1),

label: 'release',

value: 'false'

});

});

return Promise.all(promises);

})

.catch((err) => {

console.error(err);

process.exit(1);

});

}

After calling the above function, it then fetches all the items with that label. (FilterdockerResults removes anything that’s not a container, because the layers of a container are also labeled when you label a container itself). At that point, anything with a higher number is un-marked, so that the highest numbered container is still the right one to deploy.

Step 2: Update catalog

The next problem is how to get the right version numbers and edit the catalog. To do that, I had to deep dive into the catalog format for Rancher.

Any given catalog is a git repository. Inside the repository, there are a series of folders: one for each application. In each of those folders is a couple descriptive files and a series of folders: one for each version. In the version folder you have two files: a docker compose and a rancher compose. When you make changes, you are meant to put out a new folder with a new version number so that people can optionally pull in the update at their leisure. When Rancher detects that there is a newer version than the one you are on, it will display a little icon in the UI to indicate that an upgrade is available.

What I needed was a way to take an existing configuration file, change the numbers of the specific containers, and make a new version with that updated information. I could have used Regular Expressions to do the parsing, but that just smelled like the wrong solution. So instead, I added a folder called “_template” to the list of versions. Rancher will ignore this, because it’s not a numbered version; furthermore, the files inside are “docker-compose.hbs” and “rancher-compose.hbs”, which Rancher does not think it can parse. However, my Node.JS application can read these in as Handlebars templates.

This means I can write a template like this:

version: '2'

services:

nginx:

image: artifactory:5000/nginx-fram:{{nginx-fram}}

stdin_open: true

volumes:

- /var/log:/var/log

tty: true

labels:

io.rancher.container.pull_image: always

io.rancher.scheduler.affinity:container_label_soft_ne: io.rancher.stack_service.name=$${stack_name}/$${service_name}

io.rancher.container.hostname_override: container_name

fram:

image: artifactory:5000/fram:{{fram}}

stdin_open: true

tty: true

labels:

io.rancher.container.pull_image: always

io.rancher.scheduler.affinity:container_label_soft_ne: io.rancher.stack_service.name=$${stack_name}/$${service_name}

io.rancher.container.hostname_override: container_name

You see the double brackets? Those will be replaced through the templating engine with the correct version number for that container name. This is easily accomplished: I hydrate the template with an object, the keys of which are container names and the values of which are container numbers pulled from the artifactory API, as listed above:

getAllItemsByLabel (label, value) {

return request(

`${opts.uri}/artifactory/api/search/prop?${label}=${value}&repos=${opts.repository}`,

{

auth: {

user: opts.user,

pass: opts.password,

sendImmediately: true

}

}

).then((response) => JSON.parse(response).results);

},

filterDockerResults (containers) {

return new Promise((resolve) => {

const uris = containers.map((item) => item.uri);

resolve(uris.filter((item) => item.indexOf('sha256') === -1 && item.indexOf('manifest.json') === -1));

});

},

getVersions (urls) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (!urls) {

return reject(new Error('Could not get container versions from Artifactory'));

}

const retVal = {};

urls.forEach((url) => {

const [, name, version] = artifactory.parseVersion(url);

if (retVal[name] && Number(retVal[name]) >= Number(version)) {

return;

}

retVal[name] = version;

});

return resolve(retVal);

});

},

When I compose these three functions together, they get all the containers that have been marked for release, remove anything that isn’t a real container, and return only the highest numbered one of each. This makes a neat little object to pass into the Handlebars engine. I then take the hydrated template, write it out to disk as a new catalog version, commit, and push. Voila!

Step 3: Update Rancher

Now that there’s a new catalog version, I have to tell Rancher to update the stack to that version. First, I tell it to poll the catalog for updates. I do so with this neat little function (note the bonus fun comment):

refreshCatalog: function(environment) {

log('Refreshing Rancher catalog');

//This API is synch, so it won't return until the catalog is refreshed

//...in theory

//I'm pretty sure the above is a lie. A vicious, vicious lie.

//But it is the lie told to me by my ancestors, so I will repeat it.

return request({

uri: `${opts.url}/v1-catalog/templates?action=refresh`,

auth: {

username: opts.auth[environment].key,

password: opts.auth[environment].secret

},

json: true// Automatically stringifies the body to JSON

});

},

Since the function was definitely returning well before the version showed up in the catalog, I wrote a wait for this particular step:

waitForCatalog: function(catalogId, version, environment, stackName) {

update('Waiting for catalog to show up', 'info', stackName, environment);

let that = this;

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

//Wait for the service to finish upgrading

let retries = opts.retries.catalog;

let secondsBetweenRetries = 3;

function checkCatalog() {

that.refreshCatalog(environment)

.then(() => request({

method: 'GET',

uri: `${opts.url}/v1-catalog/templates/DealerTire:${catalogId}`,

auth: {

username: opts.auth[environment].key,

password: opts.auth[environment].secret

},

json: true

})).then((body) => {

let versionList = body.versionLinks;

if (versionList[version]) {

log('Found version', 'info', stackName);

log('Catalog update took ' + (30 - retries)*secondsBetweenRetries + ' seconds.');

return resolve();

} else {

retries--;

log(`${retries} retries remaining`)

if (retries < 0) {

log('Did not find version in catalog. Check Bitbucket?');

return reject(new Error('Timed out waiting for version to appear in catalog.'))

}

setTimeout(checkCatalog, secondsBetweenRetries * 1000)

}

});

}

setTimeout(checkCatalog, 500);

});

},

This is basically the same as the waits I mentioned in part 2, of course, just waiting for the version to show up in the catalog instead of waiting for the service upgrade to finish.

Once the catalog entry is showing up, I can submit a stack-level “upgrade” action. Since I knew I’d also have to do a “complete” action and a “rollback” action, I went ahead and genericized this function as well:

performStackAction: function (stackId, environment, action, body = {}) {

return request({

method: 'POST',

uri: `${opts.url}/v2-beta/projects/${opts.projectIDs[environment]}/stacks/${stackId}?action=${action}`,

body: body,

auth: {

username: opts.auth[environment].key,

password: opts.auth[environment].secret

},

json: true

});

},

Now, in the case of an upgrade action specifically, you need to pass the compose files into the API. I’m not sure what happens if they disagree; this catalog portion may not be strictly necessary if the passed-in configs are preferred. That said, we knew we wanted the record in the catalog, and it’s easy enough to hand it the same data we just wrote to disk a moment ago.

performStackUpgrade: function (stackName, environment, newnum, composes) {

update(`Upgrading ${stackName} in ${environment} to version ${newnum}`, 'info', stackName, environment)

return findStack(stackName, environment).then((body) => {

if (body.data.length <= 0) {

throw new Error(`Could not find stack ${stackName} in ${environment}`);

}

let stackId = body.data[0].id;

let catalogId = getCatalogId(stackName);

return this.performStackAction(stackId, environment, 'upgrade', {

dockerCompose: composes.docker,

rancherCompose: composes.rancher,

externalId: `catalog://Dealertire:${catalogId}:${newnum}`

}).then(() => stackId);

});

},

The “externalId” key is what’s telling it that we’re doing a catalog upgrade. However, passing in blank composes results in nothing changing; it won’t read them out of the catalog to determine what to change. It’d be great if it did, though, hint hint.

We then wait for upgrade in much the same way we did when updating a single service, then report success back to the user. The overall sequence thus looks something like this:

return updStack(`Upgrading stack ${stack}...`, 'pending')

.then(() => gitLib.clone())

.then(() => gitLib.config())

.then(() => updStack('Creating new version...', 'pending'))

.then(() => artLib.getContainers())

.then((urls) => artLib.getVersions(urls))

.then((versions) => gitLib.update(catalogID, versions))

.then(retval => {releaseData = retval})

.then(() => gitLib.commit(`Release for ${stack} on ${releaseData.internalID}`, catalogID, releaseData.folder))

.then(() => updStack(`Created version ${releaseData.id}. Waiting for update...`, 'pending'))

.then(() => ranLib.refreshCatalog(env))

.then(() => ranLib.waitForCatalog(catalogID, releaseData.id, env))

.then(() => updStack('Performing upgrade...', 'pending'))

.then(() => ranLib.performStackUpgrade(stack, env, releaseData.folder, releaseData))

.then((id) => releaseData.stackID = id)

.then(() => updStack('Waiting for upgrade to complete...', 'pending'))

.then(() => ranLib.waitForActionCompleteStack(releaseData.stackID, env, 'upgraded', stack.display))

.then(() => updStack('Waiting for health checks...', 'pending'))

.then(() => ranLib.waitForHealthCheckStack(releaseData.stackID, env, stack.display))

“updStack” here is my function to send a message back through the websocket to the client; git is my git library, artLib is the artifactory library, and ranLib is the rancher library. You have to wait for health checks here or you’ll run into issues if you complete the upgrade right away, but again, that’s pretty straightforward.

Deploybot

The interface to my final product, therefore, is really straightforward: a password prompt with AD authentication so only our Operations team can deploy, then three buttons per application. This screenshot was taken during the initial rollout; we have dozens of applications now, each with their own set of three buttons. Ops will do an upgrade, then leave the stack in the upgraded state while they confirm that the application is running correctly; when that’s done, they can complete or roll back, according to the test result. All the functionality for rollback and complete comes from Rancher; I’ve just exposed it here in a series of handy buttons to avoid them having to dig through the UI in an emergency or at 3 in the morning.

Is it overcomplicated? Yeah, totally. There’s a lot I plan to change in version 2.0, which will probably need to be tweaked when we upgrade Rancher and move to a Kubernetes-backed system. But it gets the job done, and after the first few weeks of finding edge cases and smoothing them out, it works like a charm. Sometimes that’s what you’re looking for in a devops world: a reliable, straightforward tool that gets the job done so you can get back to releasing new functionality.